[DevOps] Should you migrate onto YAML release pipelines?

Lets be honest: if by today you still have classis build pipelines in Azure DevOps (you know, the ones you click together) it might be a nice New Years resolution to migrate onto YAML pipelines. YAML-based pipelines are maybe a little bit less starter-friendly to set-up, but once you’re used to them the benefit of being able to tightly couple your build definition with your code is priceless.

So what about release pipelines then? Once YAML-based (build) pipelines had all of the kinks ironed out, the product team started targeting release pipelines as well. Up to the point where the yaml-based pipelines are now references as “consolidated pipelines”, meaning they can do both. And although they can, in my opinion there’s still a few kinks left in the release part of this story.

Stages

Instead of saving this for the end of the article, I’m going to start with the most important one. In most companies where I’ve worked with DevOps, we always had a multitude of environment to which our software needed to be deployed to. DTAP (OTAP in Dutch), as we often refer to, stands for Development, Test, Acceptance and Production. So that’s 4 different environments, to which you need to deploy your software.

Example of Stages in classic Release Pipelines. The green checkmark indicates a succeeded deployment, a green box indicates that’s the release that’s currently deployed from that particular stage.

Within YAML, there’s support for stages. As the product team wants us to use YAML pipelines for both build and release, a stage doesn’t really have a clear cut definition other than “a specific part of your pipeline”. So if you only do build steps you can just as well split those into stages which can each run on different agents, in parallel, etc.

Ok cool, so for our 4 different environments we could use separate stages. But in almost every situation I’ve encountered, we weren’t doing full continuous deployment, but instead continous delivery. The difference? If you’re boasting about your continous deployment, I would expect that each commit automatically ends up in Production without any human interaction. For none of my customers this was ever true. There’s always someone pressing additional buttons in order to deploy stuff onto subsequent environments. To be clear: I don’t think that’s an issue in most cases. But it does imply that we need a button to press.

Environments

And that’s where YAML-pipelines become an issue, cause by default they do not have that button. By default, all of the stages simply run after each other as long as there were no previous failures.

Luckily, there’s a solution for this which is called: Environments. Creating an Environment allows you to specify policies for it, which include Approval. Ok, it’s not exactly the same as the “deploy” button we have in classic release pipelines, but at least it’s a button you need to press and it blocks a release from deploying without manual interaction, so kind of the same. But it’s not the same. There’s more to the Deploy button in classic release pipelines, for instance the ability to redeploy a specific environment, which you do not get in YAML-pipelines. At least not out of the box as far as I know it.

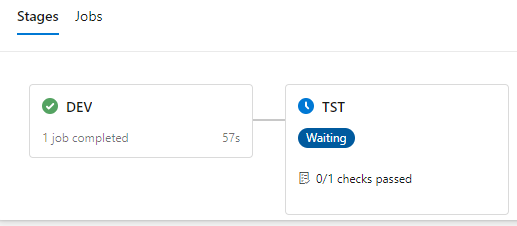

Example of stage approval within a yaml-based pipeline. This allows you to keep a release from automatically propagating to the next stage / environment.

Another issue with these environments, is that you’ll need one for every stage in every release pipeline you’ve got. For my current customer that would imply at least dozens of environments. Luckily you do not have to create these by hand as the pipeline editor in DevOps can do that for you. But still, you’ll have to set-up the approval policies for each one and one way or another; each environment brings a little bit of maintenance with it. Top tip: make sure you have proper approval groups in place which you can reuse over environments to ensure your not manually adding in individuals in each environment. You’ll thank me later.

And lastly, the Environments feature really gives me the feeling it wasn’t designed for this use. By default, an environment contains either virtual machines or Kubernetes namespaces. Not WebApps, Functions or other things you might want to deploy to. And so in most cases when used this way, you’re environment will remain empty which feels a bit weird.

Dashboarding

So suppose you work around this all and you’re bound to set-up your release pipeline. Stages, Environments, everything is configured and your pipeline is deploying like crazy. At some point in time you or your team will have the need to have an overview. Especially when you’ve got multiple pipelines set-up. So, what then?

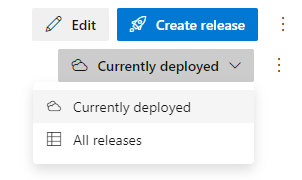

Classic Release Pipelines offer the ability to filter the currently deployed release. Especially in teams which deploy multiple times per day this can be quite usefull. There’s no such option (afaik) for yaml-based pipelines.

Unfortunately, most dashboard widgets in DevOps that cover the topic of releases have been built on top of Release Pipelines. So they’re basically useless for yaml-based pipelines. You can use the build-targeted ones, but those probably won’t show you what you want to see. So unless you want to venture onto the custom route, you’re left out of options.

Is it all bad?

Reading all this might have left you thinking: ok, so we’re not doing yaml-based pipelines for releasing. But hold on, there’s another side to this story. The benefits why we’ve moved from classis build pipelines to yaml are obvious and those same benefits apply to release pipelines as well. It’s super nice to be able to pair up changes in your codebase with related changes to your release process. This is especially true when you’re also deploying infrastructure as part of your product.

Also, the way you can group reusable steps into a template is in my opinion a lot better than the task groups we had before. So there’s definitely benefits as well.

Conclusion

All things combined, I’m not sold on yaml-based release pipelines…. yet! There’s a lot of promise here and I would definitely like to have yaml-based release definitions just like we have for build. But it’s simply not feature complete at this point if you ask me. There’s too much lacking. It might be fine for a simple deploy-to-Azure-Web-App scenario, but more complex and multi-environment pipelines quickly become cumbersome. Just as the lack of proper dashboarding options.

It could be that I’m missing options here. So if I am, please point those out in the comments below. But for now I think I’m keeping my release pipelines in the classic version, hoping that improvements are just around the corner.

December 22, 2021 at 3:06 pm |

Hello Jasper,

I’m a long time reader and i’m a bit surprised regarding your opinion on YAML pipelines.

We’re using it on dozen of customers for multiple environments and we clearly don’t want to go back.

I agree that the design of “deploy_job” in order to be able to use environments could have been better (why not using the “job” feature ?).

Also, if you want a deploy button, you have so many ways to do it that there’s one that may fit your needs (pipeline triggers on tags or pull requests, environment approvals, the manual approval task https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/devops/pipelines/tasks/utility/manual-validation?view=azure-devops&tabs=yaml, webhooks and so on …). You can also have the approval button in your Slack integration 🙂

Also, as you mentioned,you can use templates in order to have common tasks/jobs/stages/pipelines in your whole organization.

Also, we’re combining the YAML pipelines with the Terraform provider for Azure DevOps in order to have a full infra as code support. Since the provider does not support all the Azure DevOps feature, you can combine it to the REST API provider https://github.com/Mastercard/terraform-provider-restapi

December 22, 2021 at 3:11 pm |

Hi Laurent,

Thanks a lot for your comment and I really value your insight as a user of yaml pipelines yourself. To be honest I purposely picked a side for this article to see whether readers would agree or not and you definetely don’t it seems 🙂 That’s good and something I can learn from. I’ll take your suggestions and will try them out to see whether that changes my opinion. Thanks for your reply and for being a long time reader, I really appreciate it!

Cheers, Jasper